This Week in Space 129 Transcript

Please be advised this transcript is AI-generated and may not be word for word. Time codes refer to the approximate times in the ad-supported version of the show.

0:00:00 - Tariq Malik

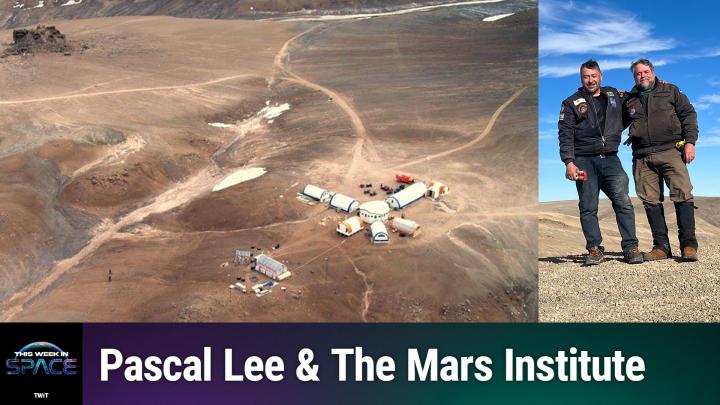

Hey space fans. On this episode of this Week in Space, we're welcoming back Dr. Pascal Lee from Mars, where we're going to talk about his latest expedition to that Arctic palace and his thoughts on where we should really be landing on the moon. Check it out.

0:00:17 - Rod Pyle

This is This Week in Space, episode number 129, recorded on September 20th 2024. Back from Mars. Hello everyone, and welcome to another episode of this Week in Space, the Back from Mars edition. I'm Rod Pyle, editor-in-chief of Ad Astra magazine, and I'm joined, as always, by the eclectic Tariq Malikik, editor-in-chief of that most prominent space news website, space.com. Hello, my friend. Hello, you're on a boat, rod. You're on a boat. I'm on my boat, yeah, the only one that counts, the expensive one. And uh, bless us. We're joined today by friend of the show, Dr. Pascal Lee. Lee, our favorite planetary scientist. Talk about his well, among other things, his summer research season at the Haughton-Mars Project Field Station in the high Arctic and the Artemis program to the moon. Hello doctor, hello.

0:01:16 - Pascal Lee

Hey, call me Pascal, but good to be here.

0:01:20 - Rod Pyle

Glad to have you in one piece. Before we start, I want to remind everyone to please do us a solid make sure to like, subscribe and do all the other podcast things that'll keep us well on the air as much as we're on the air, because, um, we need your support, so be sure to to track our, our podcast and download it all the time. And now a space joke, this one, interestingly, from Janet's planet. Does anybody remember Janet's planet?

0:01:46 - Tariq Malik

yeah, Janet, uh cavendi and iby yeah, okay, yeah so yeah, so she.

0:01:51 - Rod Pyle

She did a a long series of interstitials for pbs years ago for kids about space. She still does that stuff and so she has a joke page. Oh, hey, tark, yes, rod. What did mars say to Rod? What did Mars say to?

0:02:05 - Tariq Malik

Saturn. What did Mars say to Saturn? Give me a ring sometime. Ah, I love it. I love it. That's great, that's great.

0:02:14 - Rod Pyle

Why is our producer shaking his head All? Right let's try another one.

0:02:17 - Tariq Malik

You got a ding.

0:02:18 - Rod Pyle

Wait, I have a second one. What did the Martian say to the gardener? What? What did the Martians say Take me to your weeder. And John just left the room.

0:02:32 - Tariq Malik

Okay, I got really quick. I got a nice Janet story actually for you, because she was at the I think it was the Arrokoth flyby with New Horizons way back when you know, like it was over New Year's Eve, and I was there with my daughter she was really young back then and I had to go to like some press event. I think it was. Brian May was doing like a talk about the mission and his 3D science plan, but she was doing like crafts and so Janet watched Zadie like in the middle of this overnight middle thing as part of like a whole kids craft thing, and then I found out later that Zadie was like on stage doing all sorts of stuff with Janet. So it was a lot of fun. So thank you, Janet, for both the jokes and watching my child during an historic Kuiper Belt flyby.

0:03:20 - Rod Pyle

You have been touched by greatness. Now, getting back to our jokes for a moment. I've heard that some folks walk outside and howl at the worm-slash-sap-slash-crow supermoon, which you can see only in April when it's joke time on this show. But you can help save yourself from being mooned by our humor. Send your best, worst or most indifferent space jokes to twisttwitcom. That's T-W-I-S at twitcom, all right.

0:03:46 - Tariq Malik

Now, quick, quick correction, quick correction April's full moon is the pink moon, not the crow moon. But I digress, go ahead.

0:03:55 - Rod Pyle

The IAC said that's what it was, and there's.

0:03:59 - Tariq Malik

They all have different names. They all have different names. Well and they're all goofy and multiple and astronomy organizations don't do clickbait. But I digress. Oh my gosh, let's get through some. Also, rod, I am going to introduce for a second it's dot tv, not dot com I've been saying that for two years.

0:04:18 - Rod Pyle

Oh, my god I'm so sorry.

0:04:20 - Tariq Malik

You usually say dot tv.

0:04:22 - Rod Pyle

I thought do, I Do.

0:04:23 - Tariq Malik

I yeah.

0:04:24 - Rod Pyle

Okay, well, hey everybody, tv All right, let's jam through these headlines, because Pascal has a lot to tell us. So, Polaris Dawn is back. Everything worked fine. We got some pushback on social media from people saying, hey, that wasn't a spacewalk, that was a stand-up EVA. That's not good enough. And it's like look, nobody's done an Ed White float 30 feet from the spacecraft since Ed White and Gemini 4.

0:04:48 - Tariq Malik

So the important thing is they were safe. They wanted to Jared Isaacman wanted to and apparently, like he did say before they even got into space that when they did a lot of the testing they couldn't get comfortable with it. This is like spacex's big tentpole private space flight customer. I don't think they want him out there dangling at the end of a 30-foot tether, uh, or or even, you know, floating free so, and first test of that eva suit exactly exactly you know I'm not sure if everyone noticed, but they have a tether that is also in umical and it slots into like a connector on the top of their right thigh, on the front of the spacesuit.

So and it's a really interesting kind of quick disconnect that they came up with for this suit. But it's not like it's in a place where they could have like a lot of free range of motion and the tether is not that long place where they could have like a lot of free range of motion and the tether is not that long. It's not long enough to go all the way out, because they wanted to, you know, preserve the, the, the integrity of everything on this first one. Maybe on the next one he's got two more flights on the docket. Maybe they're gonna, they're gonna go longer. He'll get outside and do all sorts of fun stuff. We'll have to wait and see. But they, they came back. You're right, we had this story at space.com but everyone has been covering it around the world. In fact the crew in the last three days has been making the circuit on CNN, on NBC, on ABC, talking about the mission, talking about with the people that they were like the, pardon me with the people that they were raising money for.

0:06:24 - Rod Pyle

St Jude's.

0:06:24 - Tariq Malik

Yeah, st Jude's, but also some other non-profits too, to really kind of spread the love about everything that had happened. And it was just a really kind of nice feeling that that mission seems to have gone off with mostly out of hitch, and I guess the planning is underway for whatever the next flight is going to be. And uh, and we talked about it last week, I think at length rod, but um, I just there was a lot that happened. It was four people exposed to the vacuum of space.

0:06:57 - Rod Pyle

That was a bit of a record, I think yeah, yeah, it was the first for four and the first time the whole spacecraft had been evacuated above an airlock since Skylab 1.

0:07:08 - Tariq Malik

Yeah, yeah, and that's an achievement. Say what you will about like SpaceX and stuff. There's some other stuff going on with SpaceX I think we might talk about.

0:07:17 - Pascal Lee

That's next.

0:07:18 - Tariq Malik

Yeah, but it was an amazing feat and the landing appears to have gone off without a hitch. It was very smooth, the crew was smiling and just like full of joy when they came back and then they had a press conference later on in the week when they had their land legs back. So you know kudos again to Jared Eisenman and his private intrepid crew. I'm curious to see what he's going to do next with the next two flights that he has booked for the players program. He has three overall. This was the first and we'll see how long we're gonna have to wait to see what he's going to decide to do all right, and and jared does it with class.

0:07:54 - Rod Pyle

Uh, this, the whole charity angle, is something that's kind of kind of new. Other people have done it, but not to this extent.

0:08:00 - Tariq Malik

Um, it does also, but it but just a short. It does also. I think one reason they do it is because he believes in the cause. He has business before he started flying. But it does also give him a little bit of an answer when people say you know what, if you just gave all the money to St Jude's, you know, let's talk about the SpaceX F8.

0:08:22 - Rod Pyle

Pascal has a question about the SpaceX F8.

0:08:23 - Pascal Lee

Pascal sorry what. I just had a quick comment on this because I I completely agree with the fact that this mission deserves a lot of kudos and appreciation. I mean the fact that, uh, you know, we might have done from an EV strictly EVA standpoint, something that has been done before. The truth is, you know, spacex is a commercial company that is clearly developing an EVA suit system for the longer term, which will have additional complexities to it down the road, and you have to look at this test as sort of a step in the validation of different technologies and from that standpoint, that's sort of what you start with standpoint, that's sort of what you start with If you're developing a real EVA suit. You want this kind of field testing, so to speak, before you start integrating your life support system to a backpack, et cetera. So anybody who would be inclined to poo-poo this as something that was done before needs to realize that this is a big milestone in a new independent development of a suit.

0:09:26 - Rod Pyle

And it saved a whole bunch of taxpayer dollars, because we know how long it takes and how expensive these things are, and I'm sure whatever eventually is used for lunar surface EVAs by NASA will be different, but this was a big deal. Sitarik, tell us about the SpaceX FAA feud which is hanging things up Not good.

0:09:48 - Tariq Malik

So in other SpaceX news, it's been a really weird one for SpaceX because we found out earlier this week that the FAA is well. They announced that they may be levying some potential fines against SpaceX regarding to a couple of different launches in the last year, and SpaceX and Elon Musk not very happy about it. This all kind of happened around midweek, where the FAA announced that they have plans to levy something like $630,000 of fines with regards to two launches in 2023. And the issues are that SpaceX had a plan approved for launch, according to the FAA, then they put in modifications to those plans for the launch of different degrees. I don't think we have to get into it too much, but we've got details on space.com about it. But SpaceX launched anyway before the FAA had time to finish their evaluations of those changes and it happened twice. It happened during the launch of both. The launches were from Florida, but one of them was a satellite called PSN Satria from Cape Canaveral and I think it also had Echo Star 24, jupiter 3 from KSC and SpaceX says, hey, no, those changes were fine, we didn't need your approval for them. These fines are litigious and totally unwarranted.

Elon Musk said that this week they're going to sue them, the FAA, for government overreach and overregulation.

And then, I think a day or two later, they sent a really harsh letter a scathing letter, I would say, to one of the House subcommittees that oversees a lot of commercial space regulation, really just pushing on this and it's just really it's kind of like mom and dad fighting in front of the kids, kind of a thing.

You know, we're all watching this happen in real time. When we just talked about this amazing achievement with Polaris Dawn, and next week, before our next episode recording, spacex is going to launch a crewed flight for NASA Crew 9. That's the rescue flight for Sonny Williams and Butch Woolmore up on the station, so like they do have an essential service to provide. And then they're also complaining to the government about kind of launching, about the rules breaking rules that the government says they need to follow to do those flights. It's fairly confusing how that's gonna shake out, but it's just a really uh kind of fraught atmosphere right now, at least from my perspective, as like a lay person who doesn't get any of these contracts and regulations as um, perhaps as meticulously as a media space law expert would, would, would do well, I'm gonna sue you to see that you understand, the better I think that's only fair um, okay, let's take a quick break and then we will be back with Dr. Pascal Lee. Stand by.

0:12:47 - Rod Pyle

This episode of This Week in Space is brought to you by BetterHelp. What's something you'd love to learn? Gardening, maybe a new language, or how to finally beat your best friend in bowling that'd be fun. As an adult, do you make time to learn new things as often as you'd like, or was that lost in your childhood? Kids are always learning and growing, but as adults sometimes we lose that curiosity. Therapy can help you reconnect with your sense of wonder, because your back-to-school era can come at any age.

You know, I personally have benefited from therapy a number of times in my life and when you need it you really need it. And now that I can get it online, that's the best situation I can imagine. If you're thinking of starting therapy, give BetterHelp a try. It's entirely online, designed to be convenient, flexible and is suited to your schedule. Just fill out a brief questionnaire to get matched with a licensed therapist and switch therapists at any time for no additional charge. Rediscover your curiosity with BetterHelp. Help visit betterhelp.com/twis today to get 10 off your first month. That's betterhelp h-e-l-p dot com slash t-w-i-s.

Pascal, thank you for joining us. Yeah, give us a brief reminder of who you are and what you do and why you're so important. Okay, well, I'll put in the last part, if you want.

0:14:08 - Pascal Lee

I'm a planetary scientist. I work at the SETI Institute, but I'm also based at NASA, ames, and of course, all the opinions I'm going to share today are my own and do not necessarily impact or reflect those of my organizations. But I wanted to say thank you for having me on your show again. It must be a slow day Never, not hardly. I really appreciate the opportunity. So that's it. I'm a planetary scientist. I work on the moon and Mars mostly.

0:14:39 - Rod Pyle

A bit on Titan, and you, not very long ago, discovered the first major geologic feature on Mars since the Mariner program a volcano.

0:14:53 - Pascal Lee

Well, it was Sourabh Shobham, a graduate student with whom I'm working at the University of Maryland. I'm based in California myself, but we've collaborated on this joint discovery of a giant volcano, and so we're still finishing the paper on it, the full formal paper on it. But it's 450 kilometers in diameter. That's LA to Vegas in diameter. It's a colossal thing and I think it escaped detection because it's sort of very deeply eroded and it blends into a canyon maze. But it's actually, once you see it, you can't unsee it.

0:15:29 - Rod Pyle

Right, and oh, by the way, also possibly partly because of that, you are now a member of the National Academies, one of their committees, which is kind of a big deal.

0:15:40 - Pascal Lee

Well, the National Academies has been commissioned, for the first time in its history, to make recommendations on what kind of science humans should do when they go to Mars, and NASA is commissioning this. Nasa is one of the customers, but it's really the American public who's the customer, and so, yes, I'm just a lucky member of this large group of people who are going through all the documents that have been published on science recommendations for Mars. We're consulting with experts, we yesterday had a town hall meeting with the broader community, and, and so all of this is to to produce, in the end, a set of recommendations that we think will will be built on on solid ground, and I'm really excited by by. You know the deliberations that are going on and I can't share any of the details at this stage, but there'll be a giant report at the end and I think, uh, hopefully it will. It will move the, it will move the how do you call that? The needle?

0:16:49 - Rod Pyle

the needle towards us going to mars so I just have one ask, which is I want to show up to testify at one of your meetings and suggest no, I'm sorry, are you laughing? Are you laughing?

0:17:03 - Tariq Malik

no, I wonder, I'm just excited. No, no, no, I'm just excited to see what you're going to say.

0:17:07 - Rod Pyle

Because I have a very special idea about giant gliders that we'll send to Mars. It just occurred to me. We'll send it to the North Pole. We're going to land on all that smooth ice and then, let's see, we'll get a tractor out, we'll drive down to the Martian equator and build an airstrip and land the rest of them, and then, when it's time to come home, we orient them all vertically and take off. Does that sound cool? That sounds familiar.

0:17:32 - Pascal Lee

Yeah, that sounds cool, Although you know, technically the effort is supposed to be agnostic in the way you get to Mars.

0:17:40 - Rod Pyle

Sorry, Dr Von Braun.

0:17:42 - Pascal Lee

The whole idea actually is to try to drive both where we would land eventually and how we would get there, and what we take with us by the science. And, of course, science is not the only thing that's at stake when you send humans to Mars. There's also resources that you want to be able to extract, et cetera. But that's a starting point. It's a starting point when could you do the best science and the best combination of science? And I think that's always a good place to start.

0:18:12 - Rod Pyle

All right. So I'm sure there's more to learn about that, but we'll wait till you're able to talk about it. So what I'd really like to hear about is how your summer season went up at the Haughton-Mars Project Base in the high Arctic we uh started our second quarter of century of work up there, wow congratulations hill season thank you season 26 huh

0:18:34 - Pascal Lee

devon island is still there. It's the large, still the largest uninhabited island on earth. Uh, you know, when you are there you are the population of devon. Uh, what I often don't say enough is is that it's also the single largest expanse of rocky polar desert. So it's not tundra there, it's what you call polar desert, so dry and cold tundra tends to be cold but wet. So anyway, devon island is still an amazing place.

This year we tested an engineering model of the drill that's going to be flown to the moon in january on the prime one mission of intuitive machines. It was the same drill actually that's manifested on the viper rover, which for now has been mothballed, which for now has been mothballed pending some solution to fly to the moon. And I like the fact that we were not just testing theoretical hardware but actually hardware, that is, you know, at this point just doing some final maturation so that we make sure it works well on the moon. So you know, when you drill robotically, it's always very challenging. The biggest nightmare for any driller is to get your drill stuck.

This is an effort that was led by Brian Glass, who's an expert in drilling automation at NASA Ames, carol Stoker, who's a well-known planetary scientist. So the two of them led a team up there, and you know scientists. So the two of them led a team up there and, uh, you know, did an incredible job at testing their drill in different types of terrain with ice in it, uh, ice at depth, uh. So so this, uh, hopefully this will prepare viper to perf. I mean the. The. This drill is called the trident drill, so hopefully this will prepare trident to really work well, uh, on the moon.

0:20:26 - Rod Pyle

Trident drill. So hopefully this will prepare Trident to really work well on the moon. And John, we have some links to images of his Arctic base up on line 3536. So it's kind of cool to see it, because you swear when you're there, you know. Besides the fact that you can breathe on a pressure suit and your eyes don't pop out of your head and you're not being cooked by radiation, it really does feel like you're on Mars. It's pretty amazing. So can you give a little more detail about that, because we had talked about this offline? I mean, there's an element of suit testing going on with a new prototype pressure suit and also drone work this summer, right?

0:21:08 - Pascal Lee

uh, yes. So another thing we we did this summer with a collins aerospace concept space suit, uh, which we had on devon island. We we were testing how you would set up a seismometer on the moon or mars. And you know, setting up a seismometer is actually quite a tricky thing. We did that a little bit on apollo, but they were very basic in terms of their, their design.

A really good seismometer is something that you want to couple very well with the ground. The term is coupling, you want you want it to to meld with the ground so that any ground movement that occurs is actually transmitted to your detector, to your seismometer, and so you know to what extent can a space shoot allow you to sort of do this work properly of digging a shallow hole, putting your seismometer, filling the hole in, wrapping the seismometer with compact soil. All of this is something that is an EVA operation that has to be practiced, trained for and learned from. So we've just begun doing this and I think it's something that will be of great interest to NASA down the road. This is work that we're doing with a company called Fleet Fleet Space. They're based in Australia. It's one of the space startups in Australia that actually was one of the fastest growing companies in Australia just last year, I think Fleet Space fleet space Pascal, I have a question that's probably not going to be about the actual work that you did, but I'm wondering how Apollo.

0:22:53 - Tariq Malik

I'm wondering how Apollo is doing and if they defended you from any polar bears while you were out there, apollo the wonder dog.

0:23:04 - Pascal Lee

Apollo is my wonder Dog. He's my space dog. He did not go to Devon Island this year so you were overrun by polar bears then right.

Well, we, we actually were very well armed, and then we kept most of our activities very close to camp uh. But that's not the reason why he didn't go. He didn't go just because, uh, the field season was relatively short, the you know. You know, to take a dog to the Arctic there's quite a bit of paperwork involved, and and then meanwhile I had broken my, my wrist, uh, in an unfortunate road accident with my motorcycle. So, anyway, it became a bit too much to to do. At the same time I have to handle the dog, you know, on travel. So apollo was quite happy to actually stay home in california hey, were you wearing a helmet cam when you crashed?

0:23:52 - Rod Pyle

No, negative.

0:23:53 - Pascal Lee

No, there's not. Oh, too bad. That's video To the spectacular moment in my life.

0:23:59 - Tariq Malik

Planetary scientist. Mars mission simulator, right Polar bear fighter.

0:24:07 - Rod Pyle

National Academy's participant.

0:24:08 - Tariq Malik

National Academy's, you know. Martian volcano discoverer Mars volcano discoverer and now a motorcycle chopper aficionado. So you get cooler every time you're on the show, Pascal.

0:24:24 - Rod Pyle

Yeah, he gets a couple inches taller every time I see him and I'll just add we got to go to break. But I'll just add very quickly you took, was it one grad student or two this year with you?

0:24:35 - Pascal Lee

We had the two graduate students, one who was working really closely with me, the other one was working with the drilling team and with this grad student. Actually, I should say this we were flying drones and essentially trying to figure out what are the types of geologic features that would be most appropriate to explore with a mars helicopter, because we're going mars helicopter here in the years to come. It's it's been such a success with ingenuity. Jpl is planning a next generation mars helicopter and you know, one of the questions is, of all the options you have to explore scientifically what. What are the types of features that explore scientifically what? What are the types of features that a helicopter would would help you explore in a, you know, hugely incremental way? Uh, would provide a big increment in knowledge versus orbital imaging, for example.

So you know, if you you know gullies, for example, you know, do you learn a lot more about gullies on mars if you image them not just from orbit but with a robotic helicopter, very close up aerial views? And the answer is yes. Gullies are very hard to explore with a rover on the ground. Meanwhile, a helicopter provides you high-resolution imaging of a lot of details that are very important about how a gully forms. So that is an example of something that we we are concluding from our study this summer that gullies would be ideal to explore with a helicopter, but there are other things that might be less uh, you know useful to explore, like polygons. Polygons are something that you see on Mars a lot. You see them from orbit. When you image them up close with a robotic helicopter, you really learn a lot more about how they form. The answer is is not really so.

0:26:24 - Rod Pyle

So we have this type of feedback to provide to to jpl and other folks at nasa and the community at large all right, and I'll just add uh add that part of your expenses for one of your grad students was offset by a grant from our friends, the National Space Society, of which we are both members. Tariq, are you a member? I don't think so.

0:26:48 - Tariq Malik

I don't know. Is this a member like an organization that would have me? Is that like a Groucho Marx kind of a thing that I probably shouldn't be a member of a place?

0:26:58 - Rod Pyle

I can't tell you the details, but I recently suggested you for something uh involved with the NSS. But uh, we'll talk about that later all right, let's go to a break, I haven't begun thanking our sponsors.

0:27:10 - Pascal Lee

But you're right, national Space Society was really enabling and it's uh support of our project this year to to allow the student to come up, in fact, he was awarded the hmp apollo fellowship. Oh wow, to my dog, but after the apollo I was gonna say after your dog. Your dog has a fellowship but, uh, maybe it's time for a break, you're right?

0:27:30 - Rod Pyle

yeah, let's roll into a break and we'll be right back I don't know.

0:27:33 - Tariq Malik

I think the dog is the the greatest example oh hush, you stand by.

0:27:38 - Rod Pyle

This episode of This Week in Space is brought to you by Veeam. Without your data, your customers trust turns to digital dust. That's why Veeam's data protection and ransomware recovery ensures that you can secure and restore your enterprise data wherever and whenever you need it. Veeam is trusted by over 77% of the Fortune 500 to keep their businesses running. With digital disruptions like ransomware strike On October 1st, join Veeam, the global leader in data resilience, for the 2024 Veeam on Data Resilience Summit.

A world without data is one that grinds to a halt, but data resilient organizations don't let the threat of cyber attacks or disruptions define them, because they put the plan, the expertise and the solutions in place to keep their businesses running no matter what. When you join the virtual VeeamOn Data Resilience Summit, you'll learn about the industry's leading playbook to keep your data safe, protected and available, keynote-worthy news about Veeam's latest product updates, how to take full control over where and how your data is stored, and the best practices from data resilience experts who are leading the way. Go to Veeam.com to register and join for free online and don't miss their VeeamOn Data Resilience Summit on October 1st.

0:28:55 - Tariq Malik

I actually I have a Mars volcano adjacent question that I wanted to run by you, pascal, from some news that came out over the last week and a half, and you're like the only Mars volcano discoverer I know personally, so I thought I would ask you live on the podcast here. But there was a conference out in Europe, the Europlanet Conference. Every year they have it and you get a lot of really fun planetary science discoveries that get announced. And I was really struck by this study that my colleagues at space.com wrote up about these researchers who pieced together a bunch of different observations from Mars Express, from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, exomars, and then kind of compared them with the Mars InSight mission, which our listeners might remember was NASA's big Mars seismographic mission to look for Mars quakes etc.

And this study that came out said that they found what looks like a thousand mile wide plume of magma underneath Olympus Mons and that it's growing. And you know they were asking, oh, maybe it could like erupt one day. And I'm just curious if that's something that future Mars astronauts need to worry about. You know where they're, like exploring the biggest you know solar systems, uh, volcano, uh. And then all of a sudden like oh my gosh, it's like a vesuvius type like thing that that now they have to deal with on another planet. Um, are we in danger of volcano? Uh, volcano eruptions from mars right now.

0:30:31 - Pascal Lee

So let me answer this, but I'll just pre preface my answer by saying there are actually quite a few scientists who, before me, have found volcanoes on mars, but to be fair, they've been usually very small, you know the scientists or the volcanoes?

0:30:48 - Tariq Malik

I don't know the volcano.

0:30:50 - Pascal Lee

They've been kind of the volcanoes, although sometimes large clusters of volcanic, you know, in a volcanic field. Uh, but anyway, I'll. I'll move on to your question, which is really good. Yeah, that's an astounding discovery and in fact it's. It's really the type of discovery that I'm being made today, because they they synthesize data sets from different missions and different types of instruments, so there are gravity surveys that are involved here, there's there's seism activity associated with InSight, which has been very successful, and so all of this is leading these scientists to conclude that there could be a swelling mantle plume still underneath Olympus Mons, in a large magma chamber. That, to me, is both super exciting not not surprising but at the same time, uh, really exciting. Okay, because, uh, yes, olympus mons, for volcanoes on mars to be so big, these giant volcanoes, they must have been active for the bulk of mars's history, which means that the fact that they're not erupting at this minute most likely means that they're not erupting at this minute most likely means that they're just dormant, a bit like mount st helens was dormant before it blew up. Uh, many of these large volcanoes on mars are likely just dormant. They're, they're active. They might have had phases of activity that were higher, higher activity levels in the past, and so they might be sort of in the in the petering state of their lives, but they're not dead yet. And so the last eruption on Olympus Mons depending on whether or not you believe the dating of lava flows, could be as recent as about 10 million years ago, which, of course, on the scale of how Olympus Mons itself is, which is probably upwards of two, two and a half to three billion years, means that you know it's probably still an active volcano.

We've been looking for things like hydrothermal vents, you know, do you see fumaroles? Do you see things that are happening even when a volcano is not erupting, that are signs of activity, are happening even when a volcano is not erupting, that are signs of activity? Uh, this reminds me of Bill Hartman, the scientist who you know figure out the origin of our moon. Uh, he also worked on Mars quite a bit, and Bill Hartman has this beautiful painting, which I, which I own at home, of astronauts, uh, discovering a smoking volcanic vent on Mars.

Okay, and and so that to me, is still in the realm of possibilities we would not necessarily be able to resolve, you know, spatially, in imaging a smoking vent, there could be basically hidden Yellowstones still in some of the calderas of Mars in there. Wow, and so I'm. I'm just, uh, I think the odds of astronauts being ever affected by volcanic eruption are extremely low. I mean, you know, even if they were occurring on a time scale of a million years at a time, you know um it, you know the odds of us in count, you know, witnessing a volcanic eruption with a very, but on the other hand, it could be spectacular, it would be amazing.

0:34:01 - Tariq Malik

We didn't talk about it, but Olympus Mons is the largest volcano in the solar system. It's like 13 miles high. The top of it right pokes out of the upper atmosphere of Mars, so it's no small potatoes when it comes to off-world volcanoes. I guess any volcano in the solar system. But thank you. Thank you, pascal, it's the tallest, tallest, tallest. You're right tallest.

0:34:26 - Pascal Lee

Sorry, but yeah, it's all good.

0:34:28 - Tariq Malik

I'm a short guy. Anything that's taller than five feet is tall for me.

0:34:35 - Rod Pyle

All right, let's take another ad break and then we'll be back to talk about the Artemis project. So, pascal, I feel like I'm pulling a rope starter on an outboard to get you started and I'm going to rev it up to full RPMs. So we've talked a lot about the Artemis project to land Americans on the moon, hopefully before 2030, hopefully before some of our competitors get there, at least in the minds of some and it's been a long, winding road for Artemis. It's been, if you count the constellation program which you sort of have to, because that's when hardware started it's been about two and a half times longer than the Apollo program.

0:35:15 - Tariq Malik

18 years, but it's also on a 18 years. Yeah, but it's also on a 18 years yeah.

0:35:19 - Rod Pyle

But it's also on a significantly tighter budget and, at least in theory, it's supposed to be sustainable, although I kind of see that shrinking bit by bit as they move forward with plans. But you've got some thoughts on Artemis, so take it away.

0:35:34 - Pascal Lee

Yeah, there's a side of me that is loving the fact that we're going back to the moon, uh, that nasa is, has so much expertise that is being put to bear on this return to the moon and so much good work is being done, uh, but I, I have all along pretty much, but I'm being maybe a little more, you know, convinced of that and vocal now that I think strategically, uh, we, we, we may not be doing something that's optimal, with autonomous astronauts targeting the south polar regions of the moon up front. And you know, in when you look at how we explore extreme environments, even just on earth, the, the basic strategy always is to set up a base in a place that's easy to get to, reliable, to look low, low cost to operate in, safe to operate in, easy to get to, um, not necessarily located in the most exciting place, but if you can find a good place that still has excitement locally, that's great. But the key thing is not just to think of a base as a, as a fixed asset, but to think of the base and its mobility system that you equip it with as really your, your, your infrastructure, your asset. And so you know the us, for example, has mcmurdo Base as a fixed station, but then it has aircraft of all kinds of categories, like C-130s for long-range hops, twin Otters for short-range helicopters for even shorter range, and then ground vehicles as well snowcats that take you to the South Pole, et cetera. A really good strategy in general in exploration, especially programmatically, so that you have a long-term program that sustains itself and keeps things exciting, is to set up a base up front, and meanwhile, what we're doing here with Artemis is sending astronauts on sortie missions to the South Polar region without knowing really where we can extract water down the road, and it's not something that the astronauts themselves will be able to figure out, or even with the data that they bring back.

Uh, let alone uh, the idea of somehow setting up a base and building up an infrastructure at the south pole, south Pole regions of the moon, first of all, are very challenging to explore. The terrain is not at all flat, it's mountainous, uh. Second, the lighting is super challenging, uh, because the sun is very low, so you have shadows that are essentially deadly for you. Uh, you know, if you are caught in a shadow for more than an hour or two, you are essentially running into trouble with your uva systems. There is water ice in associated with the subsurface, but also in some of these permanently shadowed regions, but it's not like we can really go in there. We would have to send robotic assets in there, uh, and and then meanwhile we don't really know where we can actually find water that will be economically viable to extract.

And this is a point that I really want to emphasize Everybody is rushed.

There's a gold rush, there's a water rush, there's an ice rush to the south pole of the moon, but it's largely predicated on wishful thinking, because, while there is hydrogen and, we think, water ice in some abundance in the South Pole region of the moon and the North Pole as well, it's not like it's huge amounts.

Uh, when the L cross mission crashed into the permanently shadowed region of cabius crater, which was one of the hydrogen, the richest one of the shadow region that was richest in hydrogen, it came up with a number that's of order five percent by volume of water ice in the regolith. Okay, now, that is not very large, and even if one could extract it, even one, if one could send excavators into these craters that are at minus, you know, uh, 150 to 200 degrees Celsius, even if you could extract, uh, water ice. It doesn't mean that you can really make use of it economically, right, because it's not just excavating the ice and exposing it to the vacuum, it's it's sort of containing it, preventing it from something let me just ask real quickly, pascal, because I agree, I think, and I think we all would that we're not ready to use any kind of in situ resources like water, ice.

0:40:09 - Tariq Malik

So the argument oh, we'll just go and we'll land at the South Pole and we'll make oxygen and rocket fuel and it'll be that easy. I think we all know that that's not the case. But I was just curious because our listeners might forget what NASA's kind of plan right now is. They want to build this gateway station in a rectilinear orbit, so a really weird orbit around the moon, and then they want to build an initial base camp somewhere in the Shackleton Crater area of the south pole of the Moon, and then they want to build an initial base camp somewhere in the Shackleton crater area of the South Pole of the Moon. But they've also kind of tried to say that the reason they want this orbit is that they can then go to different parts of the Moon.

So from my kind of my and the whole timeline right now is really inflexed Artemis II, with the first one with astronauts, is supposed to launch maybe a year from now as we're recording this September 2025, and then maybe the crewed mission in 2026, but we really don't have a lander yet for that or the space suits yet for that or anything. So we have to take that with a grain of salt with that timeline. But I guess the question that I had about your concerns overall is that that kind of strategy suggests that the station is the base camp rather than the South Pole to say that we can go to different places. Nasa's argument is we've been to the equatorial region of Mars with all the Apollo missions. That's, you know, done. We want to do something new. That's done, we want to do something new. But is that kind of approach to pick an orbital base that then select different spots to do a new thing kind of not the best for science?

0:41:46 - Pascal Lee

I think those things serve different purposes. The near rectilineal halo orbit maximizes the visibility time of the south polar region, the way it's designed currently for an orbital asset to serve as a relay and also to launch back and forth from. But if we're talking about setting up an infrastructure at the surface of the moon, which is really what we want to do to really allow lunar exploration and to expand and fan out, you really want a base at the surface of the moon because you need vehicles, you need maintenance, need garages, you need robotic surface robotic assets that you're going to be fixing you, you, you do what we do at scientific, you know research stations here on earth in antarctica, the, the gateway, is a bit like a ship. You can explore Antarctica just by going there and remaining off the coast with a ship, but you're not now positioned to really have and control a large set of ground assets and capabilities that allow you to really explore the continent. You at some point have to create a beachhead, uh, which is exactly what a base is. All these antarctic stations are places from which you fan out then to explore the rest of the continent with a mobility system. So I would tend to decouple these things.

I I tend to view gateway as sort of a comms convenience and, yes, if you are really hung up and gung-ho on doing sortie missions to the lunar South Pole, that's one thing that it can help achieve. What I'm trying to get at is that I think sortie missions with humans to the South Pole is premature. We should really dedicate our entire effort, with robotic exploration, to visiting all these key sites that we've sort of pseudo-identified at the South Pole and the Moon, where we might be able to access water. Really, the South Pole is so challenging that it's the perfect realm for robotic exploration and high-risk exploration. Meanwhile, human missions should be entirely focused on setting up a base, an infrastructure that can then grow, with mobility systems that will allow you to expand, and that base, at this point, does not need to be at the south pole.

In fact. Uh, this is why I have this background behind me. I've been working on some papers and started publishing these, where clavius actually turns out to be a really exciting place where you could set up a base. And so you know, it's it's not for the fun of science meeting fiction. It turns out that Augustine Clark had proposed Clavius for for some good Earth visibility reasons and, uh, you know the fact that it has. It's a large flat area and it's near the south.

0:44:36 - Tariq Malik

You have to you have to expand on on the sci-fi connections with a clavius crater uh in the moon and arthur c clark, because our listeners might, uh might, not make that connection. Do you want me to squeal like a monolith? Why don't you go? Why don't you go ahead?

0:44:52 - Rod Pyle

give everyone the cliff notes about clavius crater and the moon and arthur 2001 space odyssey uh, clavius is where the moon bus goes to, and I guess that's act two. And uh, they discover the monolith the same monolith that was on earth, correct?

that's right it seems a big signal to jupiter, and that gets us to go to jupiter and boy, that space program looked really good compared to what we ended up getting in the 21st century so, just to to adjust what you just said, clavius was the main base on the moon, but they discovered the monolith away from that base.

0:45:25 - Pascal Lee

They discovered, like, in my view, the monolith discovery site is exactly sort of the mining situation for water ice in case we find a place where it's economically extractable. All of a sudden, you, you develop a mind in in these you know, sci-fi movie it was. You found a monolith, uh, and the shuttle went, was ferrying astronauts from the main base, from klavius base, to the monolith discovery site, the moon bus, yeah, so, so, yes, if, if, if we find a place on the moon where we think that not only that we can extract water, but where it would actually be economically viable to get the water from. Versus the other alternate. So here's the thing the alternate to getting water on the moon is to fly it in from the earth.

Now, that sounds a probably expensive, but when you think about it, a single Starship landing on the moon. One Starship is going, and that's part of everybody's plan at this point, uh, when, well, maybe not at Blue Origin, but when Starship lands on the moon, uh, and I'm not necessarily a fan of that particular design for the moon, or even for mars, for that matter, but that's a different discussion. Uh, when starship lands on the moon and we believe it can it can land in one fell swoop 125 metric tons of water, clean, purified water. You don't have to process it. It's now sitting on the moon in a water tower.

0:46:59 - Rod Pyle

You have a tap at the bottom, you have, you have clean water and you can recycle it, which is what we do with water anyway yeah, every time you say this, I I think of of the Starship looking like a huge percolator sitting on the surface of the moon with this little hose bib at the bottom that you walk over and oh man, someone has to make one of those that makes coffee in the top bubbles with a little light.

0:47:20 - Tariq Malik

Hey, I would love that.

0:47:22 - Rod Pyle

More product placement for space.com. Sorry, pascal, we got to jump to a spot, an ad spot, and we'll be right back. Stand by everybody. Okay, please finish your thought.

0:47:32 - Pascal Lee

I would just like to help plant the seed of some, you know, taking a step back and thinking about what we're doing here from a sort of a strategic level. You can land 125 metric tons of clean water anywhere you want on the moon with a starship once it gets going, and you can do a lot with 125 metric tons of water if you're recycling it. Now, of course, that's not producing fuel on the moon, but that is really something that is still very speculative at this stage. What I'm trying to say is that we should decouple our short-term human… you know, missions to the moon which really, strategically, should be focused on setting up a base, a long-term infrastructure and assembling a mobility system that will allow you to explore the rest of the moon from. We should decouple that from sending astronauts at this stage, which is pretty premature to random locations at the south pole of the moon, where, sure, they will always do some good science, uh, but you could do good science pretty much anywhere on the moon at this stage, uh, and you know, if you really want, the holy grail is branded as returning samples from the south polycon basin. Well, we can do that with a robotic rover. There's a magnificent robotic mission called endurance, to 1000 kilometre traverse across the South Polican basin that can actually collect samples and return them.

So, from from a strict standpoint of satisfying your immediate scientific curiosity, it's not even optimal for scientists to really see the Artemis missions go to the South Pole, the moon. It's in fact a bit in the way of getting a lot of science return up front versus robotic missions that could really do this very well. Meanwhile, humans are best at setting up a base, at exploring with vehicles and all this, and that is not something we can do safely or easily at the South Pole. And NASA headquarters will tell you well, well, we're going back to the moon, uh, to do things. They're not more difficult, they're just different. At the south pole it's. I don't think that's true, I think that's. That's sort of kidding yourself. Uh, things are are actually really higher, much higher risk at the moon in ways that are not very useful, because, again, you don't even know if, down the road, you you'll be able to extract the water from the South Pole of the Moon.

0:49:53 - Rod Pyle

Sorry, when you say more difficult, you mean at the South Polar region, right? Yes, yes, that's sort of.

0:49:58 - Pascal Lee

You know, to me it's not just that we want to shy away from a challenge, that's not at all that I mean, setting up a base at Clavius is going to be a huge challenge, but to me it's a much better long-term strategy on the Moon. And why Clavius? I should mention a few things. First of all, it's one of those places where on the Moon molecular water has been detected right at the surface. So actual detection of the water molecule at levels of 400 parts per million have been detected in the regolith at clavius.

Second, in conjunction with clavius is a very young crater called rutherford, and rutherford is about 30 kilometers in diameter, but it has.

It has uh, caves in it, uh, and in fact, student, some students and I are mapping these caves are caves both inside rutherford and outside Rutherford, in the ejecta blanket, which is quite, you know, amazing. In addition, there are there, it's along the path of a Tycho ray, which is such an important thing, because Tycho crater is this bright crater that you see, with rays fanning out from it. We have a sense of its age. From the Apollo samples we really would like to confirm its age and beautiful. Clavavius ray crosses, tycho ray crosses, clavius crater. In addition, there are craters of different ages throughout, and Clavius itself is the second largest impact crater on the near side of the moon and one of the oldest impact craters on the near side of the moon. So you really have a place that's super rich scientifically and would be about a few hundred kilometers of driving to the South Pole, once we know where we want to go at the South Pole and are setting up a mining camp.

0:51:44 - Tariq Malik

Or you could have hoppers right. Well, I guess I understand and this is probably my last question for you, pascal I understand that there's like a lot of scientific targets, of opportunity, you know, at a different spot to set up research station at Clavius or another site than a really rough and ready kind of the space version of a moon tent where you only can bring down the really rudimentary testing equipment. I understand that and it makes a lot of sense the way that you describe it. I'm just curious, though, what the concern or the response on the scientific side would be, because NASA is not the only agency that wants to send people to Shackleton, to the South Pole. China says they want to do the same thing. Russia has said that they've teamed up with China with their International lunar research station to do that and to have a remote station that is a home base to send robots then to the South Pole.

Some folks might say well then they're ceding the in-person science to these other agencies that are going to lock it up or whatever block access't know, we don't know. That's still far in the future. Someone has to get there first for us to test that stuff. But is that not a compelling case to make sure that we have that beachhead at the the polls, um, you know you know, here's the thing about that.

0:53:28 - Pascal Lee

First of all, setting up a large infrastructure like a base. First of all, the base doesn't have to be large. We're not talking necessarily about a moon base, alpha here.

0:53:39 - Tariq Malik

With a dome and everyone can walk around with shirt sleeves right.

0:53:42 - Pascal Lee

We're talking about starting with a small base, like we have in Antarctica. You start with a small base, it grows eventually, but the key thing about that is that it's not a limitation to science. We will tend to sometimes, you know, hear me say this and sort of say Well, you know, this is all logistics. What about the science? That it actually serves science much better to have a base. I mean, you know, we will not do the quality of science that we do in Antarctica, antarctica or even in the Arctic with our own project. We've set up a base. That's why we are in our 26th year of operation at HMP, because we're not flying to some different location. That's slightly different from the previous one each year. We have a base and a mobility system. We have vehicles which then allow us to fan out, and so it's a real powerful scientific strategy to establish a base in a place that's accessible, inherently interesting, but from where you can access other places down the road. But second, this notion that china and russia are going to team up to set up a base near the south pole of the moon. I actually would be very surprised if they actually went for the south pole of the moon. Uh, I actually would be very surprised if they actually went for the south pole of the moon, and I don't think that's actually in their plans. They might have said this, just like you know, we say we want a base at the south pole of the moon, but we don't know where we want the base of the south pole still, and um, and in any case in terms of occupying the place. Well, if you have robotic assets at some of these key locations, you know they, right there, benefit from a don't disturb clause. So, uh, you know you could multiply the amounts of robotic assets you would want to places where, down the road, you might be interested in setting up shop and you would protect them that way by having a robotic asset there.

Uh, so, and let me, let me say one more thing. You know how powers everything, how do you power all this? And we sort of drawn to these very peculiar particular locations near the south pole that are somehow permanently sunlit or have the advantage of, you know, having solar power 80 of the year. Uh, but that is, first of all, not a really good strategy at all. You don't power a base with solar panels. I mean, you know, think of every starship landing, kicking up all the dust that it will and launches. What's that going to do to your solar farm? Think of the maintenance of your, of your solar panels.

And then it talk about moon to Mars. You're not going to power a base on Mars, definitely with solar panels. And then talk about moon to Mars. You're not going to power a base on Mars, definitely with solar panels. Already, with Perseverance and Curiosity, you've moved to nuclear. So I think that a base at Clavius. The big question that comes up is well, how would you power that? Because now you have 14 days of continuous daylight. You can use solar for that, potentially, but then what about the 14 days of night? What about a?

0:56:34 - Tariq Malik

movable base Pascal, like the Haley, how, like Europe or the British Antarctic survey, they can move that base around to different places. Maybe nothing as big like that, but is that even viable as a potential for something like a movable lab?

0:56:54 - Pascal Lee

That adds huge amounts of complexity. That adds huge amounts of complexity and in some sense it defeats the purpose of having a base. A base is not something that anchors you to one location. It's a base plus its mobility system. So your base, you want it to be in a place that's wide, open, expandable, uh sure, close, close enough to sites of interest. But what makes sites of interest close enough is your mobility system. So you know, it's almost the case that you could set up your base anywhere on the moon, as long as you have the means for global access. And setting up a base at the south pole of the moon is predicated, you know, because of the complexity you have to deal with. It's predicated on this gamble that somehow we will be able to economically extract water, ice from the moon, and that, to me, is not at all a done deal. It's not at all a done deal.

0:57:50 - Rod Pyle

All it takes is a couple of sticks of dynamite and a little wisp of oxygen. That's how we did it in the old days in california blow that stuff up, you put it in an airtight cooler and boom, you got water. Okay, and it's not just about scooping out the ice right.

0:58:05 - Pascal Lee

It's not just about scooping ice out the ice and excavating Once it's exposed in these 50 degree Kelvin permanently shadowed regions. First of all, what kinds of robotics have to be built to withstand and operate in those kinds of cold temperatures? But beyond that point, once you have exposed the ice, how do you isolate it and then pipe it? You have to take it to a place where you are actually set up. I mean that in itself is a huge challenge to take it to a place where you are actually set up. I mean that that in itself is a huge challenge to pipe water through a permanent shadow region at 50 kelvin. Uh, I mean, you know the energetics.

None of that works out, or at least has been worked out, and I I keep hearing that. But you could do this, you can do this, you can do. And the question is, yes, you could possibly do it. But then ultimately, what is the price per per liter of water? What is the price of per gallon of water? And you know, does it cost less, ultimately, than 125 metric tons per starship landing, even if starship has to refuel? You know, be that as it may, 15 times, 15 times.

And and and you know, maybe far down the road we will get into some sort of a plausible economic solution to this, but it's on a completely different timescale from what we need to do now, which is to set up a fixed base on the moon, and we should do that in a place that's, I mean, not hung up on clavis. I'm just saying that it's a very good place. We're comparing it with other locations right now and, uh, so far it stays at the top by far, actually, in terms of nice places to be.

0:59:44 - Rod Pyle

Uh, so anyway, I don't know if I should be worrying, but I just saw two attack helicopters heading towards santa monica, which I've never seen down here in five years of being in this marina. This has been wonderful and we want to have you back to talk more about Mars and also to get your trademarked N equals one talk, because I've really enjoyed that and we'll have to figure out. You know how we can jump in and ask questions every now and then, but we unfortunately have to sign off, which I hate to do. But I want to thank everybody for joining us for episode 129. We're coming up on 130 here I don't know what that means, but it sounds impressive of This Week in Space, the episode called Back from Mars. Pascal. Where's the best place for us to stalk you on the interwebs?

1:00:35 - Pascal Lee

uh, where's the best place? I'm on linkedin I. I I'm on twitter at pascali tweets. I used to be on facebook, but I'm not on facebook anymore. Um, what else? Yeah?

1:00:47 - Rod Pyle

that's it all right, andk, where can we find you howling at the dryworm supermoon these days?

1:00:54 - Tariq Malik

Well, you can find me at space.com, as always Very excited. We've got a Rocket Lab launch the same night as we're recording this episode, plus maybe a Starlink launch, so that'll be something to keep an eye out for. If you're very interested in the Andromeda Galaxy as well as playing Fortnite, I got a new video at space drawn plays all about the new Andromeda galaxy skin and the actual galaxy and I'm going to be playing with that that game through the weekend Cause Iron Man's in the game, so it should be a lot of fun.

1:01:21 - Rod Pyle

Also, the Twitter that that your gameplay will certainly further our efforts for human space flight. And, of course, you can always find me at pylebooks.com or at adastra.com, where we do our best to keep you engaged. Don't forget, you can always drop us a line at twis@twit.tv. I said it right twis@twit.tv. And we welcome your comments, suggestions and ideas, and we do answer. I answer each and every email, new episodes of this podcast published every Friday, as you know, on your favorite Podcatcher, most of them. So make sure to subscribe, tell your friends and give us reviews. We'll take whatever you want to give us. And don't forget, of course, you can get all the great programming with video streams on the TWiT Network ad-free by joining Club TWiT, and there are some extras there that you'll only find there. John, do we have the video of Tariq falling out of his chair? Oh, my gosh, firmly pinned there, because that was a great clip.

Twice, I fell out twice in the chair, twice, I don't know. I have to find that In two episodes. Well, Tariq, we may have to reenact that moment. We will not lot. I fixed the chair, I paid like 80 to get extra spare parts for a 10 year old chair a 10 year old chair that you can't get anymore for less than about a grand by the way, because I looked that's right, that's right.

Star trek, and so I don't have a star trek chair. Um, anyway, join Club TWiT because, uh, unlike spending 80 in Tariq's chair, you can get this for only seven dollars a month and, although the the levels of entertainment may be about equivalent, you'll love Club TWiT. So join us, support us, come along for the show, and you can also follow the TWiT Tech Podcast Network at Twit on Twitter and on Facebook and twit.tv on Instagram. Thank you, Tariq, thank you Pascal, thank you audience, and we'll see you next time, take care.